#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <seccomp.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/mount.h>

#include <sys/resource.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 3) {

printf("usage: seccompctl <python|perl> source_file\n");

exit(-1);

}-

Let's build an online code sandbox!

-

I’ve always found the idea of sandboxes fascinating, so I tried to figure out how it’s built. After some reading, I ended up building my own sandbox system, Minival.

What you are reading right now is the commented source for this sandbox, which also serve as a tutorial of sorts about sandboxing.

You shouldn’t need to have more than some passing knowledge of C and UNIX syscalls to understand this tutorial, so let’s jump right in!

What’s a sandbox?

Simply put, a sandbox is a restricted environment that lets you run 3rd-party code without any risks. For example, browsing the web usually doesn’t crash you computer or let hackers steal your personal data. That’s because your browser runs Javascript code in a sandbox, to prevents it from doing dangerous things (mostly).

What we’re going to build here a similar, but simpler type of sandbox. We want to let people run simply Python and Perl scripts on our server. Because some people have a tendency to break things, we need to limit users in what they can do. Basically, we want to let people run simple scripts that will write to stdout and that’s about it. To do that there’s a couple of ways we could go with:

- we could use a language feature to limit what 3rd-party code can do (rpython or Safe PERL are examples of this).

- we could ask the operating system to restrict what the program can do. It’s hard to break out of a sandbox if the OS kills the process whenever it tries to do an I/O operation.

- we could do some complicated static analysis of the code. Google’s NaCL uses this approach.

-

1/ is hard to implement because we’d have to think through every possible way people could use Python to break out of the sandbox. 3/ would require an expertise about assembly and binary that I don’t have.

That leaves us with 2/ – using OS primitives to somehow constrain processes.

-

After reading a lot of Stackoverflow questions, I found out that there really are two ways to limit processes:

- use ptrace(2), a debugging interface that lets you peek around a process

- use seccomp(2), a Linux-only system call that lets a process define a whitelist of system calls it’s allowed to make.

-

Seccomp is a little more interesting. It was created back in 2005 to let people rent out their CPU (!). Over the years it added the ability to define pretty fine-grained rules that the kernel will use to limit access to resources.

Seccomp seemed a bit better at the time, even though it didn’t really have a good Python interface, so I ended up writing everything in C.

How minival works

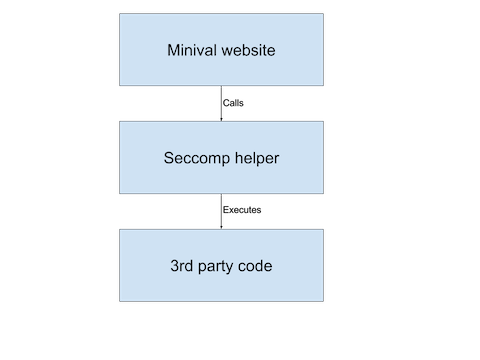

Minival is a pretty straightforward Python webapp – people type code into a form, select a runtime then submit it. Behind the scenes, the Python app spawns a helper process that does all the sandboxing setup, and then runs the untrusted code:

-

The helper will setup some helpful limits and then call execve(2) to run a Python or PERL process. Once the limits are set, the 3rd-party code is effectively restricted to the whitelist of syscalls we defined.

-

Let’s start by including a bunch of UNIX includes

-

First, we have to setup some CPU and memory limits. We use the setrlimit(2) syscall for that. We have to do this before setting up the sandbox because we do not want people to be able to change them after that the sandbox is running.

-

Limit the maximum CPU time of the process to 10 seconds.

struct rlimit rl; rl.rlim_cur = 10; setrlimit(RLIMIT_CPU, &rl); -

Let’s also limit stack and heap usage to 16MB.

getrlimit(RLIMIT_STACK, &rl); rl.rlim_max = 16*1024*1024; setrlimit(RLIMIT_STACK, &rl); setrlimit(RLIMIT_DATA, &rl); -

Setup seccomp. SCMP_ACT_KILL tells the kernel to kill processes when they make a forbidden syscall.

scmp_filter_ctx ctx; ctx = seccomp_init(SCMP_ACT_KILL); -

Let’s whitelist a bunch of syscalls. We do this by calling

seccomp_rule_addwith some parameters to match syscalls.Note that I got this list mostly by trial and error; I had to run strace on the python interpreter to see which syscalls it was making.

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(access), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(arch_prctl), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(brk), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(clock_gettime), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(close), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(connect), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(execve), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(exit), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(exit_group), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(fstat), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(getdents), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(getegid), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(geteuid), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(getgid), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(getpid), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(getrandom), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(getrlimit), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(getuid), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(lseek), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(lstat), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(mmap), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(mprotect), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(munmap), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(read), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(readlink), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(rt_sigaction), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(rt_sigprocmask), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(rt_sigreturn), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(sched_getaffinity), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(set_robust_list), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(set_tid_address), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(stat), 0); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(sysinfo), 0); -

Astute readers may have noted that we haven’t whitelisted the open(2) syscall yet. This is because we want to prevent people from creating files. To do that, we’ll only whitelist and handful of parameters: O_RDONLY, O_CLOEXEC, O_NONBLOCK, O_DIRECTORY. Because the parameters are ORed together, we have to do this on three separate lines.

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(open), 1, SCMP_A1(SCMP_CMP_EQ, O_RDONLY)); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(open), 1, SCMP_A1(SCMP_CMP_EQ, O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC)); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(open), 1, SCMP_A1(SCMP_CMP_EQ, O_RDONLY|O_NONBLOCK|O_DIRECTORY|O_CLOEXEC)); -

Python also tries to make so local socket connections when starting – so let’s open up sockets but only if they’re local.

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(socket), 1, SCMP_A0(SCMP_CMP_EQ, AF_LOCAL)); -

Next are two one-off rules for PERL.

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(fcntl), 1, SCMP_A2(SCMP_CMP_EQ, FD_CLOEXEC)); seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(ioctl), 1, SCMP_A1(SCMP_CMP_EQ, TCGETS)); -

We also need to prevent people from writing to any files on the file system besides stdin, stdout and stderr. To do that, we let people write to file descriptors 0, 1 and 2, since on UNIX they’re the default values for stdin, stdout and sterr.

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) { seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(write), 1, SCMP_A0(SCMP_CMP_EQ, i)); } -

Now, let’s load the filter! Note that it’s critical to check the error code of this function, because we do not want to be running untrusted code because the filter wasn’t created!

if (seccomp_load(ctx) != 0) { printf("Couldn't load seccomp filter! Exiting!"); exit(-1); } -

We can now let the Python or PERL interpreters run the program safely!

if (strncmp(argv[1], "python", 16) == 0) { char *args[] = { "/usr/bin/python", argv[2], 0}; execve(args[0], (char **const) &args, NULL); } else if (strncmp(argv[1], "perl", 16) == 0) { char *args[] = { "/usr/bin/perl", argv[2], 0}; execve(args[0], (char **const) &args, NULL); } return 0; } -

Wrapping up

So, that’s about it! As you can see, it was really easy to create a secure environment for our use case. If we had wanted to go the extra mile, we could have used something like Linux namespaces to provide separate file systems, networking, etc. to the sandboxed code – which is actually what LXC and Docker do to implement containers!

If you’re curious about the whole implementation, the source code is on Github. If you’re interested in sandboxing, here’s a list of resources I found very interesting:

- an overview of the sandboxing system Chrome uses

- a presentation about pledge(2), OpenBSD’s version of seccomp and some related thoughts about seccomp from a chromium security engineer

- some old notes about the JVM sandbox

Of course, please let me know if you have questions or remarks (especially if you’ve found a security issue in the above code!) – send me an email at

hello at khamidou.com!